Chapter Four cont’d

With the turn of the 20th century, it was clear that “the Irish Question” had to be settled in a decisive way. Pressure for Home Rule was growing, and in 1905 a new radical, militant, nationalist group was formed, called “Sinn Fein,” meaning “ourselves alone,” led by Arthur Griffith. The great problem now was less that Britain wanted to hang on to its colonial possessions, and more that in the North of Ireland, the Ulster area, dwelt a Protestant majority determined to resist Catholic rule. This Protestant group, largely the descendants of the more radical Protestant settlers (mainly Scots Presbyterians) who began coming over in the 16th and 17th centuries, considered themselves both loyal members of the United Kingdom, and also authentically Irish, proud upholders of the Anglo-Irish Protestant Tradition.

In response to Sinn Fein, the Ulster Protestants formed the Ulster Volunteers, basically a citizens’ army, and pledged to resist violently any imposition of Catholic Home Rule. In response to the Ulster Volunteers, the Catholics then formed the Irish Volunteers, a Catholic citizens’ army determined to fight for Catholic Rule. (Many of its leaders came from an underground group called the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which itself grew out of the Fenian Brotherhood of the 1860’s; the eventual result of this organization would be the Irish Republican Army, or IRA, which still survives in Northern Ireland today.) A civil war seemed imminent, between the Protestant Unionists (favoring continued union with Great Britian) and the Catholic Nationalists (favoring an independent, Catholic-ruled Ireland) when World War I broke out in 1914. John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, felt that by supporting England’s war effort the Irish would encourage eventual Home Rule, and so he urged a cessation of hostilities until the Great War was over.

Yet even among the Nationalists, there was division. The older leaders felt that gradual parliamentary rulings would bring about some sort of Home Rule for Ireland, probably in a kind of commonwealth relationship to England, similar to that of Canada. But the younger members, remembering with bitterness the fall of Parnell and distrusting political policy, demanded a full split from England. This group, termed Separatists, saw England’s engagement in World War I as their best opportunity for seizing power and forcing England to release its hold on Ireland. These younger members determined that a bold and dramatic armed uprising would mobilize the population and perhaps lead to an overthrow of British rule.

Yet even among the Nationalists, there was division. The older leaders felt that gradual parliamentary rulings would bring about some sort of Home Rule for Ireland, probably in a kind of commonwealth relationship to England, similar to that of Canada. But the younger members, remembering with bitterness the fall of Parnell and distrusting political policy, demanded a full split from England. This group, termed Separatists, saw England’s engagement in World War I as their best opportunity for seizing power and forcing England to release its hold on Ireland. These younger members determined that a bold and dramatic armed uprising would mobilize the population and perhaps lead to an overthrow of British rule.

Leaders of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, as well as leaders of the Irish Volunteers, combined with James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army (a militia set up in 1913 to protect striking workers during the major transport workers’ strike and lockout that year), to formulate a daring plan. They would stage armed attacks in Dublin and other key areas throughout the countryside on Easter Sunday morning of 1916. Their hope was that the Irish citizens would flock to their banner, and additional uprisings would occur almost spontaneously. But a crucial shipment of arms, being carried from Germany to the Kerry coast by Sir Roger Casement, was lost, and the Volunteers’ leader, Eoin MacNeill, backed out at the last moment, canceling all Volunteer activity for the day of the planned rising. Nevertheless, the IRB leaders determined to go through with their plan.

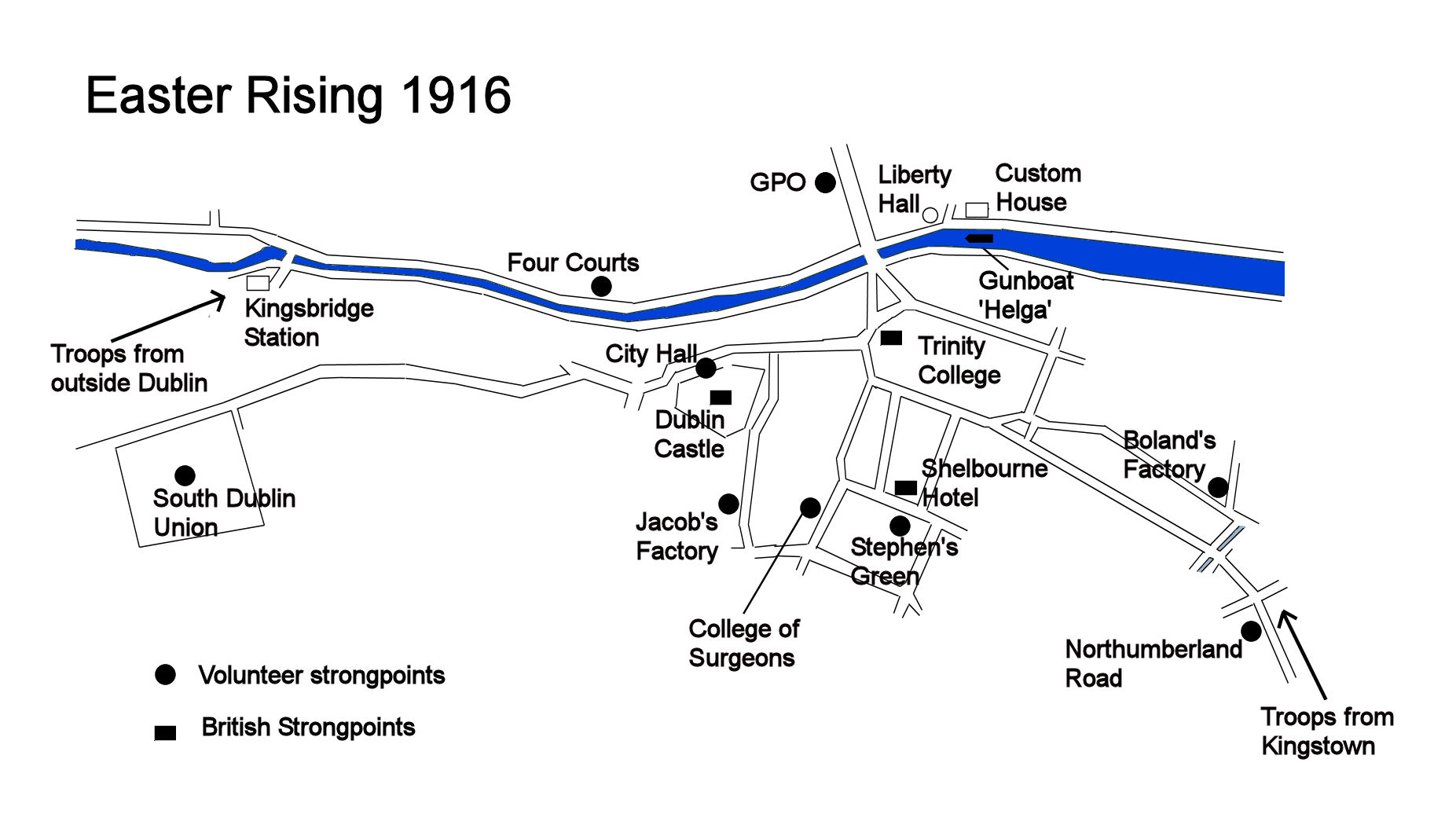

The rebels seized the General Post Office on Sackville Street, in the heart of North Dublin, and declared it their headquarters. Their leader, Patrick Pearse, read a proclamation declaring the establishment of an Irish Republic. (View the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.) It took the British army, and the Irish citizens too, some time to realize that this was a rebellion in earnest. But because the attack had not been coordinated with the bulk of the Irish Volunteers, no other significant revolts occurred throughout Ireland. The British army could turn its attention wholly to the small force in Dublin. A half-dozen or so battle sites raged throughout the city, some mere skirmishes, and others, such as the battle at Stephen’s Green, more prolonged and deadly conflicts. The British adopted a strategy of isolating the rebels’ positions, and compelling surrender one at a time. Ultimately the British brought gunboats up the Liffey River and soon they were shelling the rebels’ small outposts with full artillery and destroying entire sections of Dublin. (See image above.) The British superiority in manpower and artillery was overwhelming, and after holding out heroically for nearly a week, Pearse finally surrendered unconditionally on Saturday. 64 rebels had been killed, 132 British military, and over 200 civilians. In addition, much of central Dublin was in ruins. All the major leaders–Pearse, Connolly, de Valera, Plunkett, MacBride, and others–were captured. The Irish populace had not risen up to join the rebels, but on the contrary, many hissed and spat at them as they were taken away to prison. The insurrection seemed a total failure.

But, in one of history’s great ironies, the British themselves ensured that the rebellion would have a powerful effect. They declared Martial Law, and under its rubric many civilians were killed and wounded (including the murder by a British soldier of Francis Sheehy Skeffington, an intellectual and avowed pacifist, and one of James Joyce’s long-time friends [he is the figure of MacCann in Portrait]). The British command quickly tried and condemned to death each of the leaders of the insurrection, and between May 3 and May 12 the British executed 14 of them by firing squad. The Irish citizenry were horrified, and soon the leaders of the Easter 1916 Rebellion had become glorious martyrs, joining a long list of Irish who had died trying to free their country from the British.

View Easter 1916 Presentation by clicking the images above.

Yeats’s poem “Easter 1916” is the most famous mythologizing of these figures, and what is perhaps the most famous single event in Modern Irish history:

I write it out in a verse–

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

As Pearse waited in his cell in Kilmainham Gaol for his execution, he wrote his final poem, titled “A Mother,” which imagines a mother’s thoughts on the sacrifice of her children to the cause of Irish freedom. (View “A Mother.”)

Kilmainham Gaol Cells